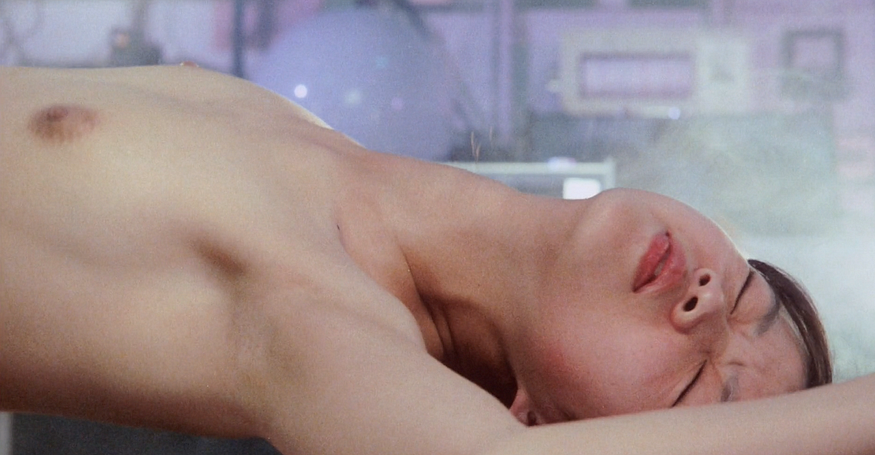

當老師把女學生放在實驗牀上時,白色的迷霧已經把女孩子帶入奇境的夢幻中。花色的布單扯下,一朵嬌艷的花蕾赤裸地呈現在老師的眼前,猶如遠古的阿爾塔米拉(西班牙語:Cueva de Altamira。位於西班牙北部桑坦德市以西30公里的桑蒂利亞納戴爾馬爾小鎮。洞內保存有距今至少12000年以前的,舊石器時代晚期的人類原始繪畫藝術遺跡)人簡潔線條勾勒出來的青春之花,動人心魄,而又讓人生出無限愛意。

實驗用的金屬探測棒,無情地插入花蕊,被迫綻放的花苞,在痛苦中,奏出最原始的花吟。無法區分現實和夢幻,唯有起起伏伏生香活色,帶我回到“素女為我師,儀態盈萬方”的遠古。

After Altamira, all is decadence。阿爾塔米拉之後,一切藝術都衰落了。

— — 巴勃羅·魯伊斯·畢加索(西班牙語:Pablo Ruiz Picasso,1881年10月25日-1973年4月8日,西班牙著名的藝術家,法國成名,和喬治·布拉克同為立體主義的創始者,是20世紀現代藝術的主要代表人物之一)

恥感文化

魯思·本尼迪克特(Ruth Benedict,原姓Fulton,1887年6月5日-1948年9月17日,又譯作:露絲·潘乃德),20世紀初的美國人類學家,女性學者,受到弗朗茨·博厄斯(德語:Franz Boas,1858年7月9日-1942年12月21日,也譯作:法蘭茲·鮑亞士。德裔美國人類學家,現代人類學的先驅之一,被稱為“美國人類學之父”)的影嚮,同愛德華·薩皮爾(德語:Edward Sapir,1884年1月26日-1939年2月4日,又譯沙皮爾、薩丕爾,生於普魯士王國倫堡[今屬波蘭],美國人類學家和語言學家)提出了文化形貌論(Cultural Configuration),認為文化如同個人,具有不同的類型與特徵。

在二戰期間,魯思·本尼迪克特受美國政府委托,試圖了解日本侵略文化的糢式,並希望找到可能的弱點,或者說服手段,解決盟軍是否應該占領日本,以及美國應該如何管理日本的問題。她通過大量的文學作品、剪報、電影和錄音等資料,運用文化人類學方法對日本進行研究,重點是分析了日本國民的性格。報告在1944年完成,在1946年整理成書《菊與刀》(The Chrysanthemum and the Sword)出版。

In anthropological studies of different cultures the distinction between those which rely heavily on shame and those that rely heavily on guilt is an important one. A society that inculcates absolute standards of morality and relies on men’s developing a conscience is a guilt culture by definition, but a man in such a society may, as in the United States, suffer in addition from shame when he accuses himself of gaucheries which are in no way sins. He may be exceedingly chagrined about not dressing appropriately for the occasion or about a slip of the tongue. In a culture where shame is a major sanction, people are chagrined about acts which we expect people to feel guilty about. This chagrin can be very intense and it cannot berelieved, as guilt can be, by confession and atonement. A man who has sinned get relief by unburdening himself. This device of confession is used in our secular therapy and by many religious groups which have otherwise little in common. We know it bring relief. Where shame is the major sanction, a man does not experience relief when he makes his fault public even to a confessor. So long as his bad behavior does not ‘get out into the world’ he need not be troubled and confession appears to him merely a way of courting trouble. Shame cultures therefore do not provide for confessions, even to the gods. They have ceremonies for good luck rather than for expiation.

True shame cultures rely on external sanctions for good behavior, not, as true guilt cultures do, on an internalized conviction of sin. Shame is a reactio nt oothe rpeople’s criticism. A man is shamed either by being openly ridiculed and rejected or by fantasying to himself that he has been made ridiculous. In either case it is a potent sanction. But it requires an audience or at least a man’s fantasy of an audience. Guilt does not. In a nation where honor means living up to one’s own picture of oneself, a man may suffer from guilt though no man knows of his misdeed and a man’s feeling of guilt may actually berelieved by confessing his sin.

The early Puritans who settled in the United States tried to base their whole morality on guilt and ali psychiatrists know what trouble contemporary Americans have with their consciences. But shame is an increasingly heavy burden in the United States and guilt is less extremely felt than in earlier generations. In the United States this is interpreted as a relaxation of morals. There is much truth in this, but that is because we do not expect shame to do the heavy work of morality. We do not harness the acute personal chagrin which accompanies shame to our fundamental system of morality.

The Japanese do. A failure to follow their explicit signposts of good behavior, a failur et obalanc eobligatio ns or to foresee contingencies is a shame (haji). Shame, they say, is the root of virtue. A man who is sensitive to it will carry out all the rules of good behavior. ‘A man who knows shame’ is sometimes translated ‘virtuous man,’ sometimes ‘man of honor.’ shame has the same place of authority in Japanese ethics that ‘a clear conscience,’ ‘being right with God,’ and the avoidance of sin have in Western ethics. Logically enough, therefore, a man will not be punished in the afterlife. The Japanese-except for priests who know the Indian sutras-are quite unacquainted with the idea of reincarnation dependent upon one’s merit in this life, and-except for some well-instructed Christian converts-they do not recognize post-death reward and punishment or a heaven and ahell.

The primacy of shame in Japanese life means, as it does in any tribe or nation where shame is deeply felt, that any man watches the judgment of the public upon his deeds. He need only fantasy what their verdict will be, but he orients himself toward the verdict of others. When everybody is playing the game by the same rules and mutually supporting each other, the Japanese can belighthearted and easy. They can play the game with fanaticism when they feel it is one which carries out the ‘mission’ of Japan. They are most vulnerable when they attempt to export their virtues into foreign lands where their own formal signposts of good behavior do not hold. They failed in their ‘good will’ mission to Greater East Asia, and the resentment many of them felt at the attitudes of Chinese and Filipinos toward them was genuine enough.

— — Ruth Benedict,The Chrysanthemum and the Sword

在人類學對各種文化的研究中,區別以恥為基調的文化和以罪為基調的文化是一項重要工作。提倡建立道德的絕對標準並且依靠它發展人的良心,這種社會可以定義為“罪感文化”。不過,這種社會的人,例如在美國,在做了並非犯罪的不妥之事時,也會自疚而另有羞恥感。比如,有時因衣著不得體,或者言辭有誤,都會感到懊惱。在以恥為主要強制力的文化中,對那些在我們看來應該是感到犯罪的行為,那里的人們則感到懊惱。這種懊惱可能非常強烈,以至不能像罪感那樣,可以通過懺悔、贖罪而得到解脫。犯了罪的人可以通過坦白罪行而減輕內心重負。坦白這種手段已運用於世俗心理療法,許多宗教團體也運用,雖然這兩者在其他方面很少共同之處。我們知道,坦白可以解脫。但在以恥為主要強制力的地方,有錯誤的人即使當眾認錯,甚至向神父懺悔,也不會感到解脫。他反而會感到,只要不良行為沒有暴露在社會上,就不必懊喪,坦白懺悔只能是自尋煩惱。因此,恥感文化中沒有坦白懺悔的習慣,甚至對上帝懺悔的習慣也沒有。他們有祈禱幸福的儀式,卻沒有祈禱贖罪的儀式。

真正的罪感文化則依靠罪惡感在內心的反應來做善行。羞恥是對別人批評的反應。一個人感到羞恥,是因為他或者被公開譏笑、排斥,或者他自己感覺被譏笑,不管是哪一種,羞恥感都是一種有效的強制力。但是,羞恥感要求有外人在場,至少要感覺到有外人在場。罪惡感則不是這樣。有的民族中,名譽的含義就是按照自己心目中的理想自我而生活,這樣,即使惡行未被人發覺,自己也會有罪惡感,而且這種罪惡感會因坦白懺悔而確實得到解脫。

移居美國的清教徒們曾努力把一切道德置於罪惡感的基礎之上。所有精神病學者都知道,現代美國人是如何為良心所苦惱。但是在美國,羞恥感正在逐漸加重其分量,而罪惡感則已不如以前那麼敏銳。美國人把這種現象解釋為道德的松弛。這種解釋雖然也包藏著很多真理,但這是因為我們沒有指望羞恥感能對道德承擔重任。我們也不把伴隨恥辱而出現的強烈的個人惱恨納入我們道德的基本體系。

日本人正是把羞恥感納入道德體系的。不遵守明確規定的各種善行標志,不能平衡各種義務或者不能預見到偶然性的失誤,都是恥辱。他們說,知恥為德行之本。對恥辱敏感就會實踐善行的一切準則。“知恥之人” 這句話有時譯成 “有德之人”,有時譯成 “重名譽之人”。恥感在日本倫理中的權威地位與西方倫理中的 “純潔良心”、“篤信上帝”、“回避罪惡” 的地位相等。由此得出的邏輯結論則是,人死之後就不會受懲罰。日本人 — — 讀過印度經典的僧侶除外一一對那種前世功德、今生受報的輪回報應觀念是很陌生的。除了少數皈依基督教的以外,他們不承認死後報應及天堂地獄之說。

恥感在日本人生活中的重要性,恰如一切看重恥辱的部落或民族一樣,其意義在於,任何人都十分註意社會對自己行動的評價。他只需推測別人會做出什麼樣的判斷,並針對別人的判斷而調整行動。當每個人按照同一規則玩游戲並相互支援時,日本人就會愉快而輕松地參加。當他們感到這是履行日本的“使命”時,他們就會狂熱地參加。當他們試圖把自己的道德輸出到那些並不通行日本的善行標志的外國時,他們就最易遭受攻擊。他們“善良”的“大東亞”使命失敗了。許多日本人對中國人和菲律賓人所採取的態度實在感到憤慨。

— — 魯思·本尼迪克特. 菊與刀

魯思·本尼迪克特把基於基督教的文明歸類於罪感文化(Guilt Culture),把日本文明歸類於恥感文化(Shame Culture)。她的分類很有意義,但是她簡單地認為恥感文化是外在驅動,即缺乏內省。這是錯誤的。日本人的恥感受儒家文化的影嚮,但又有自身的特色。

羞恥心

子曰:“道之以政,齊之以刑,民免而無恥;道之以德,齊之以禮,有恥且格。”[譯文]孔子說:“以政令來管理,以刑法來約束,百姓雖不敢犯罪,但不以犯罪為恥;以道德來引導,以禮法來約束,百姓不僅遵紀守法,而且引以為榮。”

— — 論語‧為政

顯然,按照儒學,恥辱是內在的約束。儒家文化也希望通過每個個體以“道德”來進行自我管理。

具體到人的“恥感”是如何得來的,沒有公認的明確的定義。通常的解釋是因隱私遭侵害,被他人知曉。或者自我一些不榮譽、不成功、不得體等事件,感受到與社會預期不符,或者受到他人指責,所造成的情緒、心理的感受。

日本人的“恥”具有一種獨特性,她不是因為你做了不該做的事情,而是當你做了不該做的事情時候,還從中發現了“樂趣”。如果我們深入分析,日本的“恥”,更多是因為享受了不應做的事情所帶來的興奮、快樂,甚至期望但又害怕之中的特別感受。

比如吧,你吃了垃圾食品,知道它對身體不好,但是它好吃啊 — — 事實上,所有的垃圾食品都好吃,反而健康食品中,不少是難吃的。畢竟,為了身體健康吃些難吃的食品是正常的。如果知道不健康,又不好吃還要吃,實在不符合人性。

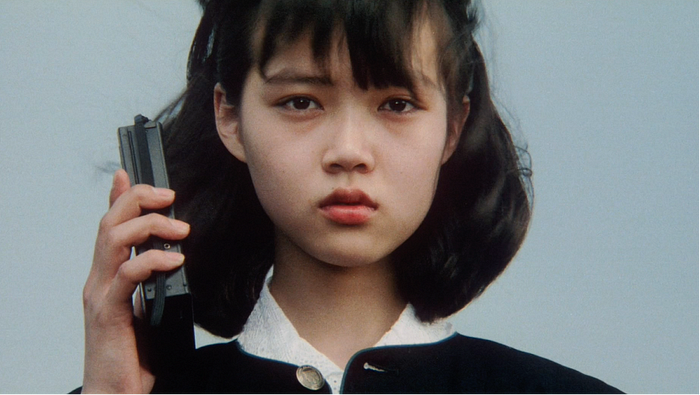

食色性也,《蒲公英》中的食色,到了《女郎漫游仙境》(The Excitement of the Do-Re-Mi-Fa Girl,日語:ドレミファ娘の血は騒ぐ ,1985。IMDb: tt0214636),就算是對色的科學實驗吧。

繁花走線,2023年2月11,14,15修改

繁花走線:被緊縛的花房

仙境中的“恥”女郎[1]·恥感文化

仙境中的“恥”女郎[2]·新自由心理研究

仙境中的“恥”女郎[3]·極“恥”實驗

關註我,我們一起看花開花落;分享我,此生艱難,唯有結緣;

— — 繁花走線